West - #38-1

Standing L-R: West, Thomas K. (P) [KIA]; Qualman, Thomas W. (N); Noesges, Thomas M. (B); Kasold, Edward A. Jr. (CP)

Kneeling Middle L-R: Deibert, Thomas E. (Arm/TTG) [KIA]; Ross, Trefry A. (RO/WG); Mergo, Joseph G. (TG) [KIA]

Seated Front L-R: Yesia, Frank C. Jr. (BG) [KIA]; Doe, Roy L. (NG) [KIA]; Gaul, Frederick H. (E/WG) [KIA]

| AAF# | Type | Group | Sq | Sq# | Nickname |

| 44-41016 | B-24J | 461 | 765 | 35 | Unknown |

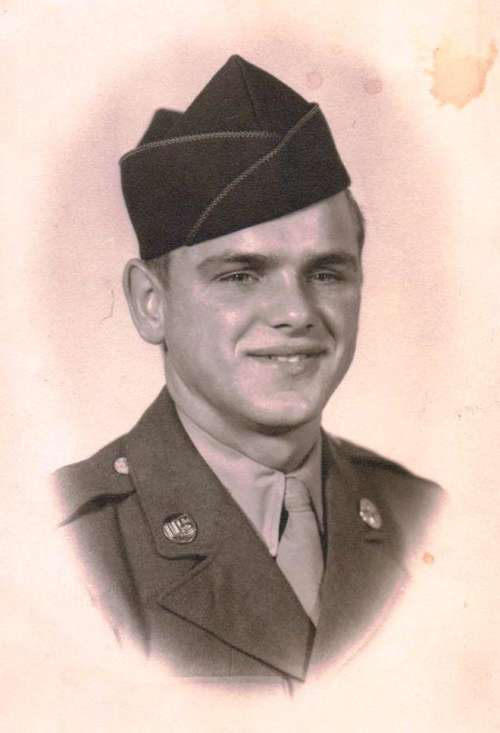

PILOT: 2nd Lt. Thomas K. West (KIA), Volin, South Dakota, Single. Sen. C. Wayland Brooks wrote to Hap Arnold

MISSIONS: Unknown

LAST SIGHTED: 1145, Muglitz

DOWN: 1230

WHERE: 49-27'N 17-27'E Prerov, CZ

2nd Lt. Donald J. Rhodes (765th), "Lt. West's plane pulled out of formation and were below us about 1,000 feet. At the time there were several enemy fighters around them, and while I watched I saw Lt. West's crew shoot down 3 of the enemy fighters. We passed them trying to catch the formation, and they went out of sight behind our right wing." Sgt. Trefry A. Ross, right waist on West's plane, "We were hit by enemy fighters about 12 o'clock. 5 minutes from the target. Our aircraft burst into flames." Sgt. Thomas E. Deibert, top turret gunner was killed by fighters. 2nd Lt. Thomas M. Noesges, bombardier, was struck in the head by a fragment from a German shell, and had no recollection of getting out of the doomed bomber. Thomas W. Qualman, navigator, "We were shot down about noon on our way north toward Germany." CZ women: "One plane fell in Troubkach in Prerova; there six are buried. The other fell in Lesne u Vel Mezirici." West, Deibert, Doe, Yesia, Mergo, Gaul died in this action.

Thomas M. Noesges

1944

15th Air Force – 461st Bomb Group (H) – 765th Bomb Squadron

Torretta Field – Cerignola, Italy

Saturday, November 4

Augsburg, Germany

RR Marshaling Yards

26,000′; -39 degrees C.

96 heavy AA guns, flak intense but inaccurate

No enemy fighters

Escort: 105 P-38s

Undercast 10/10 at 12,000′ over target

Form 1: 8 hrs. 25 min.

Bomb load: Six 500# RDX

Credit: 2 missions

Sunday, November 5

Vienna, Austria

Florisdorf Oil Refineries

24,000′; -37 degrees C.

326 heavy AA guns, flak very intense but inaccurate except when leaving target; two holes in ship

Nine FW-190s sighted; no attack

Escort: 48 P-51s

Thin 10/10 undercast at 10,000′

Form 1: 7 hrs. 50 min.

Bomb load: Seven 500# incendiary clusters

Credit: 2 missions

Tuesday, November 7

Sarajevo, Yugoslavia

RR Marshaling Yards, Ali Pasin Most

22,000′; -23 degrees C.

19 heavy guns; possible additional RR guns;

flak not to intense but very accurate; 1 hole

Expected one squadron of FW-190s; none sighted

Escort: 48 P-51s

Weather over target: 3/10

Form 1: 4 hrs. 45 min.

Bomb load: Nine 500# RDX

Credit: 1 mission

Friday, November 17

Vienna, Austria

Florisdorf Oil Refinery

24,000′; -36 degrees C.

326 guns; 88mm and 105mm; flak intense and accurate; no hits on our ship

No enemy fighters sighted but our escorts shot down Ju-88 spotter

Escort: 52 P-38s

Weather at target: 8/10 undercast

Form 1: 6 hrs. 55 min.

Bomb load: Six 500# RDX plus two 500# booby traps

Credit: 2 missions

Sunday, November 19

Vienna, Austria

Vosendorf Oil Refineries

26,000′; -40 degrees C.

326 heavy guns plus guns to south of city; flak very intense and very accurate; two holes in left wing near #2 engine

No enemy fighters; Ju-88 spotter shot down by our escort of 96 P-38s

Weather over target: 10/10 undercast

Form 1: 7 hrs. 35 min.

Bomb load: Six 500# RDX

Credit: 2 missions

Saturday, December 2

Blechhammer, Germany

Oil Refineries

25,000′; -37 degrees C.

150 Guns; flak intense and very accurate; first bursts were right on us; no hits

No enemy fighters sighted

Escort: 70 P-51s to target; 55 P-38s over target;

50 P-51s off target

Weather: 6/10 undercast over target

Form 1: 7 hrs. 55 min.

Bomb load: Six 500# RDX plus two 500# booby traps

Credit: 2 missions

Wednesday, December 6

Maribor, Yugoslavia

Marshaling Yards

22,000′; -39 degrees C.

25 guns; flak light and inaccurate

No enemy fighters

Escort: 36 P-38s

Weather: Flew in cloud layer 6,000′ thick; escort not sighted; break in clouds directly over target

Form 1: 6 hrs.

Bomb load: Eight 500# RDX

Bad icing on windows

Credit: 1 mission

Friday, December 15

Linz, Austria

Marshaling Yards North of city

24,000′; -30 degrees C.

46 guns; flak moderate and inaccurate

No enemy fighters sighted

Escort: 36 P-38s

Weather 10/10 at target; bombed PFF

Form 1: 7 hrs. 40 min.

Bomb load: Eight 500# RDX

Credit: 2 missions

Sunday, December 17

Blechhammer, Germany

Odertal Oil Refineries

26,500′; -42 degrees C.

1200 guns; 88mm and 105mm

Attacked by between 50 and 100 FW-190s and ME-109s

Escort: P-38s and P-51s

Hit by enemy fighters and exploded at 1200 hours shortly before turning on IP near Troubky, Czechoslovakia.

03:00 Sunday, 17 December 1944, Cerignola in southern Italy. Everybody up for mission number nine (actually 14 or 15 counting the doubles). “Pappy” Tom West is usually the first out of the sack. Eddie, our co-pilot is last, Navilemoque and I are somewhere in between. For most of us this is the most difficult part of combat. Not the most dangerous; just the most difficult. Not much is said as we dress, slip into our rayon socks covered by the GI woolen ones and our GI shoes. Rayon or silk under wool is the warmest combination. We gather our heavy flying jackets and pants and head for the mess hall still in silence. Probably anxious for our destination and hoping for a short one since our last one was to Linz, Austria just two days ago where we hit the marshaling yards.

The conversation picks up a little as we devour our pancakes, scrambled eggs, bacon and toast washed down with a mug of strong coffee. We all four light up our favorite brands of cigarettes as we waddle to the briefing room. It is now 0430 on a cold, damp morning. As we enter the room we look immediately to the board to see what our gas load will be for today. This will tell us the length of our mission. We gulp…2700 gallons. It’s got to be Berlin or Blechhammer - the #1 and #2 targets in Europe for us. The briefing officer enters and uncovers the map. The red lines run to Blechhammer. Our last trip there was two weeks ago with Form 1 time of 7 hours 55 minutes. That’s too damned much time over enemy territory which enables their fighters to take off from different bases and attack us. Also a long way back to our field in the event we are crippled.

It’s the oil refineries again…at 27,000 feet, 150 anti-aircraft 88s pointed at us in anger. Not to mention the Messerschmitt 109s and Focke-Wulf 190s who will be up there looking for us.

The one thing you must remember about every man on our crew, and perhaps every man on every air crew, is that we are all volunteers for this duty. None of us was forced to fly at all, much less in combat.

We are given our IP (Initial Point) which is usually a town or specific point on the map from which we start our bomb run on the target. The object of this is to mislead the Nazis to believe we are heading for a target other than our objective. I do not think they are so easily deceived. We are also given an alternate target the name of which I cannot remember.

The briefing over, we head for the parachute building to pick up our chutes. Pappy and Eddie get their seat packs and everyone else gets a chest pack. With the seat pack you always have the chute with you. With the chest pack you wear the harness and keep the chute as close as possible but you must snap it on with two “D” rings before it can be used. We also get our electric suits, flak vests and helmets with the ear flaps. We look like a pack of Cocker Spaniels.

We see the enlisted men for the first time this dark and miserable morning as we walk to our plane on the line. They are the finest bunch of guys of any crew we have ever seen or heard of. Their constant bantering and teasing kept all of us loose in some pretty tight situations. We all talk of the big party the ten of us are going to have on Christmas Eve when we open all the packages of food and goodies from home which we have been hoarding for the past couple of weeks.

I tell Roy Doe, our nose turret gunner, to check the ammunition in his boxes to make sure they are full. His reply, “Why always me…is my name the easiest to pronounce?” Incidentally, it’s not easy to write about an air crew of ten men when four of them are named Tom. I don’t feel comfortable calling people by their last name.

Our plane is getting a new magneto in #3 engine so we will be delayed in taking off and will have to do our best to overtake and join the squadron in formation to the target. After about half an hour we get the OK from our ground crew chief. Mergo, Yesia, Ross and Gaul climb into the aft section of the ship and Deibert and Doe join us in the forward section.

We taxi to the end of the runway where we get a quick green light from the control tower. We’re off and climbing…no circling for a rendezvous as we normally do. Qualman gives us a heading and we start to look for the rest of our group. It takes us 20 or 30 minutes to find them and fall into our slot in the formation. We’re on the way to Blechhammer on the Oder River along the German-Poland border.

My electric suit isn’t working properly so I grab my oxygen tank and crawl through the tunnel from the nose back toward the bomb bay and up on the flight deck with Pappy and Eddie. Everything is going smoothly with not a sign of trouble either from our plane or the Germans. Three hours go by and we’re approaching the Czech-German border…only half an hour to our IP. I’m getting ready to go back down in the nose and get on the Norden bomb sight.

Suddenly radio silence is broken by Joe Mergo, our tail gunner. “Here they come…7 o’clock high.” Joe gets in a long burst at the attackers with his twin 50s. All hell breaks loose in a matter of three seconds. Shells are exploding everywhere inside the plane. Those 20 millimeters made me feel like I was inside of a popcorn popper. I’m standing on the lower level just below the upper deck when Tom Deibert’s feet dangle from his foot rest in the top turret just above me. I pull the emergency release cable under his seat and as he falls I see he took a direct hit from a 20 mm shell.

The plane lurches upward and starts to fall over to the right. Qualman is coming through the tunnel from the nose. I don’t know how he can move. The centrifugal force is pinning everything to the floor. Eddie is out of his seat and heading back towards me. Pappy is up but can’t find his chute. The controls are shot out…our main oxygen tanks behind the bomb bay are on fire and the flames are licking at the bombs.

I reach behind me into the bomb bay for the emergency handle to open the bomb bay doors so we can jump out. The hydraulic system is out. I try to crank the doors open manually but they jam after opening only about a foot…not enough to allow us to get out. In terror and frenzy I begin to jump on the doors.

The next thing I remember is falling through space…face down…trying to snap the second “D” ring to my harness. It doesn’t take long. With a chest pack chute you do not want to be face down when the shroud lines rip out of the pack. They could change your looks in a hurry.

I casually hold out my right arm until I’m flipped over on my back and looking up at the sky. I see the rest of the squadron fading away in the distance with the German fighters diving through the formation. All I can hear is the whistling of the wind as I float down toward the earth. It’s an eerie sensation of weightlessness. My senses are coming back and I’m aware of the pieces of airplane falling not too far from me. One of my gloves blows off and without thinking I reach out for it. It’s a hundred feet away before I know it.

Now I’m starting to think about opening my chute. Don’t want to do it too soon because we heard the German fighter pilots had instructions to shoot at us as we came down and the longer you hang there the more time they have to make several passes.

I knew from our weather briefing that the cloud cover in this area topped out at three thousand feet so I decided to wait until I went into the clouds to open my chute. Since we were at 27,000 feet when we were hit, that would be a free fall of about 24,000 feet. Roughly 5 miles at 2 miles per minute.

I’m into the clouds now and my chute opens on the first pull of the rip cord handle. In a few minutes I break through the clouds and see the ground. I’m heading towards a forest of barren trees…in the worst possible attitude for a landing. I’m coming in backwards and oscillating like a pendulum. I’ll probably break every bone in my body. Remembering the parachute training (classroom only) we all had to undergo, I reach up and grab my shroud lines and try to twist them around. The chute almost collapses. Enough of that. I let go and immediately land in the trees on the edge of the woods.

As I hang there suspended between two trees about 30 feet from the ground, I see the fuselage of our plane land about a mile from me. It was almost exactly noon when we were hit…it is now 1205. I can see people running to the wreckage of our plane. It won’t be long before they see my big white umbrella in these naked trees. This is Czechoslovakia, but there are German soldiers here and they don’t take kindly to the guys who are bombing their cities and their families.

I don’t dare to try to get out of my harness 30 feet up in the air so I pull my Scout knife from the outer pocket of my jacket and cut one of the shroud lines at the top of my chute and tie it to the loop on the knife. I throw the knife over a sturdy branch about 15 feet away. It wraps around the branch several times and I pull myself into the tree. After getting out of my harness I stop to get my breath and look over the situation. It doesn’t look good. I wonder how many of our men got out. I don’t see any other chutes.

I look down from my perch. It’s a long way down even considering the distance I just fell. There are no branches to use as a ladder so I “bear hug” my way down about five feet and rest. Suddenly I become light headed and weak. I can’t hold on any longer. My grip loosens and I slide straight down the tree trunk. As I hit the ground, my left ankle saps inward at a 90 degree angle. All hope of escape is gone now.

I’m aware of a cold sensation on the back of my neck and feel back there. I bring my hand back and it’s covered with blood. No pain so it can’t be too serious. I pat myself on the head and discover a tear in my helmet. Just a little scratch I must have got in the plane but enough to cause weakness when I tried to climb down the tree.

My first thought is to bury the Colt 45 I carry in my shoulder holster. We were instructed to use the gun only to barter our way to safety not to try to fight the war with it. I scratch a hole in the six inch layer of snow and put the gun under it.

After crawling through the forest for some two hours, I am overtaken by a small band of Czech civilians. The first thing they do is take my first aid kit and my morphine which I refrained from using until the pain in my ankle got unbearable. Otherwise they were very courteous and understanding. They lifted me onto a two wheel cart and took me to a little town named Troubky where they carried me into a house and gave me some black bread and lard.

They spoke to me in German and although my comprehension was not yet good, they managed to convey to me that they must turn me over to the Wehrmacht or suffer reprisals. They assured me that the soldiers in their locality were decent men and they would not harm me but would give me medical attention under the Geneva Convention Rules of Warfare.

Around 1800 that night the German soldiers came to get me. At first they thought I was a spy because my clothing was so expensive it couldn’t be an Army uniform. The only thing that saved me from being shot was the insignia on my shirt collar and my silver wings. They took me to a barracks type of building and told me an ambulance would soon be here to take me to a Lazzarette (hospital) where they had very good doctors who would repair my ankle. While I waited for the ambulance, a German in the uniform of a sergeant of the Luftwaffe approached me and offered his hand in friendship. “I am the one who shot your aircraft,” he said in perfect English. “I am sorry for you and your friends, but for you the war is over.” I asked what type of fighter he flew. “Focke-Wulf 190,” he answered. I offered him one of my cigarettes. He accepted and together we smoked and sat in silence for a brief minute. He saluted me and left.

The ambulance came and took me for a three hour ride to what proved to be Brno, Czechoslovakia. I was carried on a stretcher to the operating room. All my clothing was taken from me and I went into surgery at midnight. Exactly 12 hours from the time we were first hit.

I awoke the next morning in a bright clean hospital room. My left leg was propped up on a little platform type of elevation. It was also in a cast. This was to be my abode for the next five months, the first three of which are lost from my memory (with the exception of what I have written in the little Wehrmacht Werkbuch Diary which was given to me).

I do remember the meals which consisted almost exclusively of a small portion of black bread, small portions of a kind of sausage, chicken broth with intestines (no meat), ersatz jam and ersatz coffee. That was it. I lost 60 pounds in those five months. Most of it from the fever caused by the infection in my ankle.

On 9 April it was decided that the Russian army was getting too close to Brno since they bombed our hospital the day before and I was hit in the forehead by a piece of glass from my window on the second floor. They loaded all the patients including me and a wounded Russian soldier who I spoke to in German, aboard a hospital train and headed toward the American lines.

The first time we were strafed by our own P-47s, the car in which I was riding caught fire and although I was close to the door, I was the last one carried out. No thanks to a six foot three SS Major who looked at me in such a way as to say “I would like to shoot you now.” The locomotive was blown up and we had to wait overnight for another one.

I don’t recall the exact date of Hitler’s birth, but on that April day aboard the train my captors gave me a short fat cigar to celebrate. I inhaled and it nearly killed me.

On 24 April, the last day on the train, our P-47s strafed us again. Again our locomotive was knocked out. We were in a railroad marshaling yard parked along side of several flat cars with brand new FW-190s on them. The “Jugs” came in so low strafing those 190s they couldn’t see the Red Cross markings on the roof or sides of our hospital train. One of the German wounded patients on the train was evacuating his kidneys in a glass bottle during the attack. A .50 caliber slug shattered the bottle during the process covering him with glass and you know what…he didn’t get a scratch. I added a few choice new German words to my vocabulary.

That night we left the train in Budweis and were driven to another hospital where I remained until the very early morning of May 9th. At 0300 hours we were loaded aboard ambulances, trucks, weapons carriers, and some wounded were strapped to Tiger tanks. A Russian plane dropped a flare over us and lit up the whole convoy like it was broad daylight. They were getting closer.

I was placed in the lead ambulance along with an SS captain, and given a bushel basket full of lard (in cans), black bread, cigarettes and cigars. One of the doctors requested that I tell my American friends of the good treatment the German hospitals had given me and that I should ask my comrades for more petrol for the convoy so that they could travel deeper into Allied territory. The SS Captain was from Roumania and seemed to be a decent sort of guy. He was somewhere around 40 years of age. He claimed to be a family man with 4 children. He was in the lead ambulance with me in the event we ran into any bands of SS troops who were, at this stage in the war, killing any Wehrmacht soldiers who were surrendering. His presence would deter any such action against our convoy…they hoped.

Somewhere around 0900 we approached American troops blocking the road. We had no sooner stopped than the rear doors on the ambulance were yanked open. An Army Captain and half a dozen noncoms stared in at me. What a sight I must have been. Down from 165 pounds to 105. No haircut for five months. No decent shave for a week. My pink shirt still coated with dried blood from the scalp wound. I was unable to speak…so they did. “Hi, Mac. How’s it going?”

The words just wouldn’t come out in English. All I could mutter was, “Sehr gut.” I don’t think they doubted my nationality but it sure must have sounded strange to them. They took me from the ambulance and put me into an Army ambulance. Before we drove away I found out my liberators were General Terry Allen’s 104th Timberwolf Division of General Patton’s 3rd Army. I forgot to ask them for fuel to help the German convoy get further away from the Russians.

I was subsequently taken to the 110th Field Evacuation Hospital in Austria, to the 198th General Hospital in Paris and from there to the Azores, Newfoundland and Mitchell Field in New York on a C-54 hospital plane. After three days in New York I was flown to Gardner General Hospital in Chicago and home.

In the small village of Troubky, Czechoslovakia in a corner of a little Catholic cemetery stands a black Italian marble monument 12 feet tall and 8 feet wide with a life-size bronze likeness of Fred Gaul, our “Put-Put” engineer, descending in his parachute which did not open. Alongside the monument is an 18 foot flag pole of the same material with a cross at the top. The people of Troubky vowed to fly the American flag every July 4th and December 17th in memory of the six young men buried here. An inscription on marble slabs in Czechoslovakian and in English reads:

Here repose American heroes after their last start

Wanderer read and announce to all

We gladly died for that you live and are free

Don’t forget us.

Two other marble slabs list the names of the men buried here.

Sgt. Fred H. Gaul

Sgt. Roy L. Doe

2nd Lt. Thomas K. West

Cpl. Frank C. Yesia

S/Sgt. Joseph G Mergo

S/Sgt. Thomas E. Deibert

Not listed are the survivors.

S/Sgt. Trefry Ross

2nd Lt. Edward Kasold

2nd Lt. Thomas Qualman

2nd Lt. Thomas Noesges

GauL Engineer, Waist Gunner

YesIa Ball Turret

DeiBert Top Turret

DoE Nose Turret

MeRgo Tail Turret

QuAlman Navigator

WesT Pilot

KasOld Co-Pilot

Ross Radioman, Waist Gunner

NoeSges Bombardier

Courtesy of Fred Willey

Frederick H. Gaul (E/WG), uncle of Fred Willey

Courtesy of Bob R

Original West Memorial

Photo courtesy of Filip Kubat

Memorial to the West crew in Czechoslovakia.

Photo courtesy of Filip Kubat

Close-up of left side of Memorial to the West crew

Photo courtesy of Filip Kubat

Close-up of left side of Memorial to the West crew

Thanks to Jaromír Otáhal.

Tree where plaque was placed.

Thanks to Jaromír Otáhal.

Plaque in tree.

Thanks to Jaromír Otáhal.

Closeup of plaque in tree.